The water crisis in Cape Town opens the debate about commodification of nature, the right of access to essential resources and public policies regarding commons. Mary Galvin, professor at the Centre for Social Change at the University of Johannesburg, explains the situation in South Africa and points out perspectives and possible solutions, including the use of citizen science and democracy

Mary Galvin was invited to speak about the use of water by the mining sector and its impacts during the Alternative Mining Indaba, on 5 February, in Cape Town. She has been studying public policies in the sector as part of the Department of Anthropology and Development Studies and in this interview she presents a clear analysis about the current water crisis in the city and also in other parts of the country. Cape Town is passing through the most serious water crisis in its history and, as the specialist explains, this is related to bad planning, administrative issues and inequality in access and use of resources.

The water crisis

The water crisis

Cape Town is a city, as the global press recently noticed in the last two to three weeks, that is suffering from a quite spectacular water crisis. In two months, the water may just not be coming out of the tabs anymore [at the time of the interview, “Day Zero” was announced for mid-April, since then, thanks to water savings, it was postponed twice, to mid-May and to the beginning of June]. What are the causalities behind the crisis, specifically what is the role of export-oriented agriculture, we have been drinking South African wines every now and then. So what is the role of the stuff we consume in Europe, the agricultural products, in creating this crisis for residents here?

The starting point is we know that agriculture takes an enormous amount of water. The percentage is something like 60-70 percent. So when you’re looking at trying to get users of domestic water to decrease their usage.. it’s tiny.

You mean even the famous swimming pools on TV?

Even those… and the amounts of water that privileged South Africans use is more than privileged Americans. And that is really saying something.

That is really impressive, more than privileged Israelis? ‘Cause I understand that they are also really good… but the dynamics is the same transnationally, right?

It’s the same thing. The sense of “my money gives me rights, If I can afford it I can have it”. And my son, who is a film buff, he is fifteen, he keeps telling me about the Titanic, when you get to the point where the guy comes out with the wad full of cash and says “can I buy the lifeboat?” I mean, if you’re a farmer or a large agricultural producer you’re in it to make the money and you are given the water. So who should be regulating the farmers is the Department of Water and Sanitation. And there is a National Water Act that gave them the ability to do that.

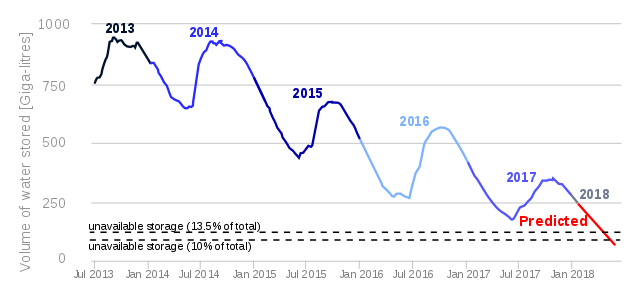

There was a secular decline that started a year ago, people started talking about this quite a while back. But nothing was actually done. How did we get here?

I think we have to be careful – what makes it into the news isn’t the whole story. There has been a lot of action on behalf of the Department of Water Affairs, they have national reconciliation strategies, they look full on into the future, where is demand? Is it increasing? Can we hold it steady, what are our supplies what are our supply-demand-curves? And they meet regularly, they look at this, they’re making plans. And climatologically they argue that no one could have seen that it could be this bad. There is scarcity but there’s also the manufactured scarcity of who gets the water.

Perspectives

Perspectives

I heard that there are basically dams outside of Cape Town that are still quite full or not as low as one would imagine in this crisis. Is this are manufactured crisis or is this a genuine crisis?

Our Department of Water and Sanitation is incredibly weak. There is a report out by the Centre of Environmental Rights spelling out corruption, mismanagement, huge vacancies, nationally. Cause there are actually six dams that feed Cape Town and four of the dams are owned by the Department of Water Affairs and the two are from the city of Cape Town. The four that Water Affairs manages are responsible for the lion share of water that reached the area. So they are monitoring those dam levels all the time and they would’ve known. So why didn’t they intervene enough? Was there political game that they were playing? I don’t think that this is a question that is easily answered, but to imply that it was some big political plot gives too much credit to all the parties involved.

What would be some steps now because clearly the idea of actually having no water coming out of the tab is terrifying. Also just the idea of what would happen between people in that situation.

The former head of Durban Water doesn’t think 2018 will have a Day Zero. He says we have to be careful for 2019, he thinks we´re panicking way too early. Regardless of what happens it’s raised a whole range of questions that people are asking and also other ones – not just for Cape Town – but for the country as a whole.

We continue to go back to the commodification of water. If you look at the most offensive devices that have been put into play for credit control in a number of townships. When you use the allocated amount for the day it cuts of, there is no more water coming out of the tab. I’m not against water management devices because something similar has been used with more success in Durban that’s basically the same technology, I think it’s how it’s used. In the Cape Town context it has been very offensive because it’s cutting off poor people for a very small amount.

I think that what we need to do in the Cape Town context and nationally is to take it away from a commodity and have the ceiling amount. So have water management devices in wealthy households to cut off hedonistic use before it reaches too far.

If we can create the spaces and have teachable moments I really do believe that we’ll see a shifting of the hegemonic approach to water. It’s been in this commodified space, when this commodification doesn’t work, when people start to raise issues, the challenge for us as activists is to say if we want to develop a different way of seeing the world rather than responding to things – what is our agenda, where we’re creating our own alternative.

I think the ground water issue in South Africa is going to need a lot more attention. What you need to know is the recharge rate and the bore holes are already making withdrawal from the ground water so those need to be registered and monitored and regulated. I’m presently working on a book that’s called “Deepening democracy or despondency” and it’s about the water sector and how citizens are engaging or residents are trying to engage with the state in different places in South Africa. So it’s not just Cape Town, in a place called Mothutlung where four water protesters were killed.

We are not going to succeed at waiting for the government to put into place legislated really there for public participation. It’s going to have to be what they call invented spaces, an opportunity, we’re creating own approaches and action.

And to make sure there is basic education, ‘cause I don’t think there is a good, I mean in Cape Town water systems quite complex with basic transfers and that. And I know I struggle to understand and I’ve been in this sector for years so I think that technically like to move it away into the citizens science where people have a basic understanding of what they are working. ‘Cause otherwise even when protests happen you are going to be protesting something you actually don’t have an understanding of. So then your target and your aim is misguided

Resistance and citizen science

Can you explain what this concept is?

Well, science in many ways is elitist, right? So how do you make that accessible to people on the ground? Citizen science is creating tools and methods so that people themselves can actively engage in the whole issue of science. A big project we did on climate change, people gathered their own data by setting up a local weather station, by mapping out weather patterns over decades using participatory tools, open data…. The hydrologists came and looked at this and were dumbfounded, they were like “they have it down to the month of the drought that was ten years ago”. My concern is more that if it’s not used properly it can also somehow become disempowering. They call it citizen science but you’re actually using the citizens just to extract information that the so called “real scientists” can use.

I think that the local sort of wars are in themselves shifting an changing things. So it’s not necessarily a bad thing. Let’s go back to what Day Zero would look like. Because I think this is the imagination that gets everyone. Like my original thing was, well are people going to show their ID? So it’s like voting. How are you going to see “you had your 50 or you had 25 litres today, okay, you’re done. No more for you”, but they are not talking about it like that at all its basically as much as you can carry…

But then the whole family has to go to work and one person is going to go to to gather the water so they can’t be there to do it. But what about the kids, the kids need water, they don’t have an ID. Logistically it is a nightmare it brings out such deep things. Of whether people intend to save the water or not. If I were here I come along with my bucket of the right side, and I would draw that water and maybe take for my children and go home and live on that. But already, the news reports are showing how the people are plotting how to beat the system to get more water.

Yesterday on the plane I spoke to a woman, she was clear, and I believed her on her saving the water. She would exactly do the same thing, she would get a jerry can 25 litres. She was really, she said “I’m already teaching my kids not to shower they wash with a cloth”. And then she talked about others from the elite who don’t behave like that. And this morning in the hotel So we took these 20 seconds showers. Then we walked out, and I stand in front of the elevator and waited for the elevator for like a minute and heard the water from a shower in another room, it was splashing, splashing all over.

And I recognize this like “oh, I limited myself, how dare you not!” and I’m thinking, can we split the elites? Revolutionary strategies only work when elites are split.There is always the possible of the contra elite and to the late 60s that sort of passed the bourgeoisie. When the elite classes are split you can actually transform the society. And I wonder, in this kind of situation there’s just thinking of… can you get those elites who are not complete assholes to join a coalition with popular movements and actually sort of, you know, work against the individual and companies that again are feral elites?

Like the whites who fought the apartheid, there were a lot, but the masses of whites didn’t fight apartheid, so I think it’s a similar thing. And also, it keeps going back to this demand thing. Because poor people are not angelic with this either.

There’s a whole debate about the right to water in South Africa versus the commons. And how we try to pursue the right to water which I still hold as the most brilliant part of our constitution. But the right to access to water, that human right is really important. As a social economic right in our constitution, the underlying question of this is how to build a common. It’s a common understanding, it’s a common respect. It’s a common respect as human beings, across income group, and I think that’s the twenty million dollar question.

* Tadzio Müller is a political scientist and climate justice activist that works for Rosa Luxemburg Foundation on Climate Justice and Energy Democracy. For more information about his work, click here. He was invited to be at the Alternative Mining Indaba by the Johannesburg RLF office. This interview was produced with the assistance of Daniel Santini, Gerhard Dilger (photos) and Marina Pinho (transcription), from the São Paulo RLF office, and Michelle Pressend, from the University of Cape Town.