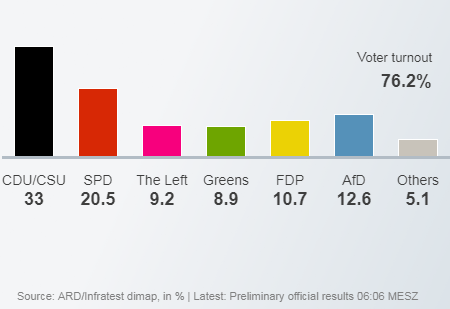

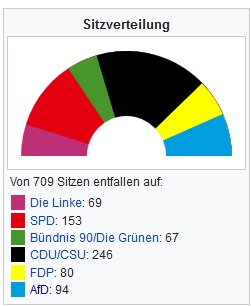

On 24 September elections for German Bundestag took place. The governing parties are the losers of this election night: together they were dinished by 13.8%. The parties “left from Christian Democrats” – SPD (Social Democrats), Linke and Greens combined – lost 4.1% and only received 38.6% of the valid votes

The downwards trend is continuing in 2017 because of the weakness of the Martin Schulz’ Social Democrats. Only in three city states Berlin, Hamburg and Bremen the red/pink/green spectrum received more 50%. In Brandenburg and Thuringia it received only a third of the votes.

The Christian Democrats (CDU) received their second worst results in the history of the republic. Reasons for that are various: another chancellorship of Angela Merkel seemed to be certain already at an early stage. Despite the party had seen a lot of criticism, retaining its power seemed to be granted which motivated a lot of conservative voters, to vote for other parties of the same camp. Obviously, for many conservative voters the transitions to the liberals and even to the right wing populist AfD (Alternative for Germany) are fluid. The diffuse core message of the conservatives “For a country in which we live in well and like to live in” might symbolise a further aspect. Even in conservative circles it’s not altogether clear anymore how this is to be understood. The CDU even lost to the AfD in Saxony.

The Christian Democrats (CDU) received their second worst results in the history of the republic. Reasons for that are various: another chancellorship of Angela Merkel seemed to be certain already at an early stage. Despite the party had seen a lot of criticism, retaining its power seemed to be granted which motivated a lot of conservative voters, to vote for other parties of the same camp. Obviously, for many conservative voters the transitions to the liberals and even to the right wing populist AfD (Alternative for Germany) are fluid. The diffuse core message of the conservatives “For a country in which we live in well and like to live in” might symbolise a further aspect. Even in conservative circles it’s not altogether clear anymore how this is to be understood. The CDU even lost to the AfD in Saxony.

The Christian-Social Union (CSU) in Bavaria loses 10.5%, reaching only 38.8% – far away from their magical 50% mark which would allow for absolute majority. The AfD gains 12.4%. The CSU did not succeed to keep the AfD small by snuggling up and taking over their positions. On the other side of the political spectrum Die Linke gains 6.1% in CSU country.

The Social Democrats (SPD) received their historically worst results in federal elections. Nothing made this more clear than the announcement to directly opt for opposition six minutes after the first results, despite their would have been a majority for continuing the existing coalition with the conservatives, and thus the implemetation of social democratic policy. Sure, it would have been a coalition of losers. At the same time this move highlights that the party is lacking strategical orientation and societal alternatives which would be worth fighting for. The candidate for chancellor could not implement his strengths as “Man of Europe”; instead he was reduced to the role of a former mayor of a small town in Western Germany. The SPD is also not safe from implosion as other social democratic parties in Europe.

The (Neo-)Liberals (FDP) return to German parliament. Their success is so closely linked to Christian Lindner that it remains completely unclear what the party stands for and what it separates from the former liberal agenda. It’s success is mainly due to the need of many former conservative voters, who wanted to vote for an alternative to the AfD.

The AfD clearly belongs to the winners of this election. It barely misses its election goal of reaching 15%. In Saxony it became strongest party, gaining three direct mandates and in other Eastern German regions it came in second after the conservatives. The East German colour scheme has changed completely. It’s completely unclear which role the nationalist, openly revisionist forces within the AfD will play, aiming at overthowing the basic rules of democratic society and possibly posing a majority in the parliamentary group. The entry of the AfD represents a political watershed in parlamentary work, becoming visible on many levels, in provocative initiatives, attention seeking action for the media and the change of political debate culture.

The success of the AfD was not surprising after it succeeded with federal issues during the preceding regional parlamentary elections. It confirms that the preceeding votes were not meant as one time protest. The societal conflict lines which the AfD increasingly pursues since 2015/16 are uniquely characteristic. The challenging debate about the future of the country has to be taken up by the other parties. If they don’t respond, as happened with the CDU in Saxony, the AfD will win all the more. In Eastern Germany it became second strongest party after the conservatives, clearly ahead of LINKE and social democrats.

The Greens come out stable. They gained more then polls predicted. The obvious orientation of the top team towards a conservative-green coalition did not damage them, rather to the contrary. They are the party of a new traditionally educated middle-class, and in many aspects, especially considering the socio-political milieus, they form the opposite pole to the AfD.

DIE LINKE remains stable as well, gains absolutely more votes than 2013 and receives the second best result in its party history. Yet, it remains below ten percent and does not get stronger than the AfD. Its votership has considerably changed. The backing in the East clearly decreased to 17.7%, in the West the party grew to 7.2% of valid votes. The power relations within the party thus change further towards the Western regional organisations. The above average approval among younger voters remains as well.

Obviously, the trend of a growing disparity between results in urban and rural areas continues. This includes an above average approval among academics. The party is on the move which altogether did not lead to a slump – thus the campaign strategy was altogether successful. The result is also suprising since the party left the game of power of future coalition forming quite early. It loses the position as strongest opposition force and will have trouble to be heard in the media compared to the bigger opposition parties. Such a stable result for a party aiming at progressive societal changes cannot be satisfying, in particular as the only possible majority option of red-pink-green has receded into the distance. Given the changed political conditions, it will now come down to overcome the existing strategical and societal obstacles to gain a wider scope of political options.

Voter turnout increased again (76.2%), reflecting a growing political interest of the citizens. The increase is not only due to formerly non-voting AfD voters.

Government formation will not become easy for Angela Merkel. The Social Democrats pursue the strategy they already tried in North-Rhine Westphalia: to force Liberals and Greens into a coalition with the conservatives. In case of a “Jamaica”-coalition the CDU will have to satisfy the party political needs of three smaller partners (CSU, Liberals, Greens). Sustainable solutions for the big societal questions are thus not to be expected. SPD and Linke as left opposition to such a government would have the option to actually form a left political alternative. In the long run, this might be the last window of opportunity for the renewal of social democratic and left reformist policy.